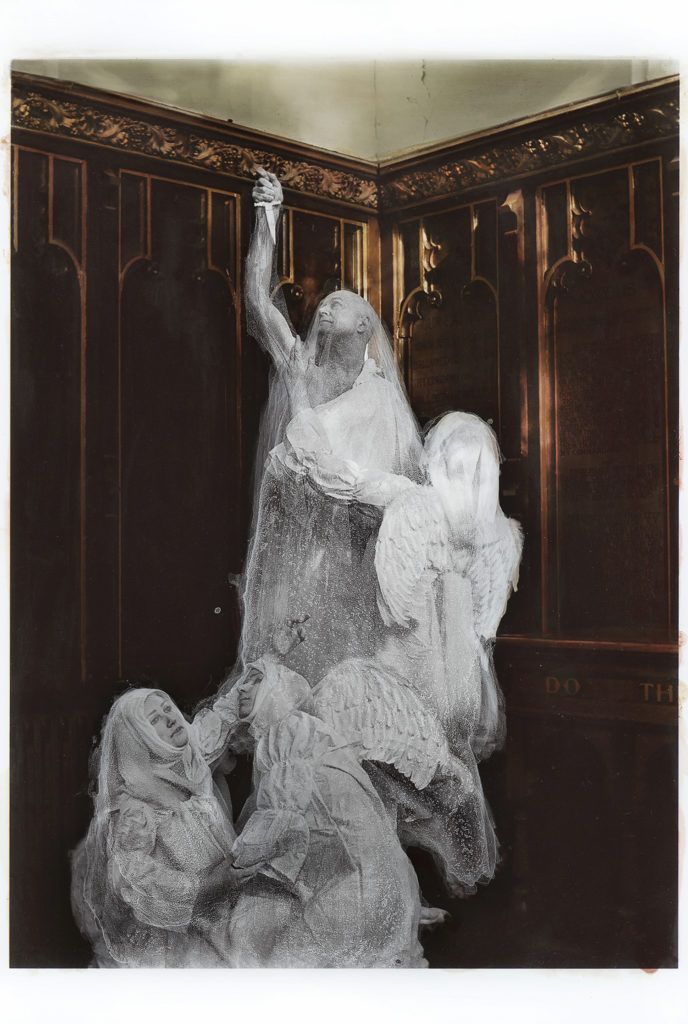

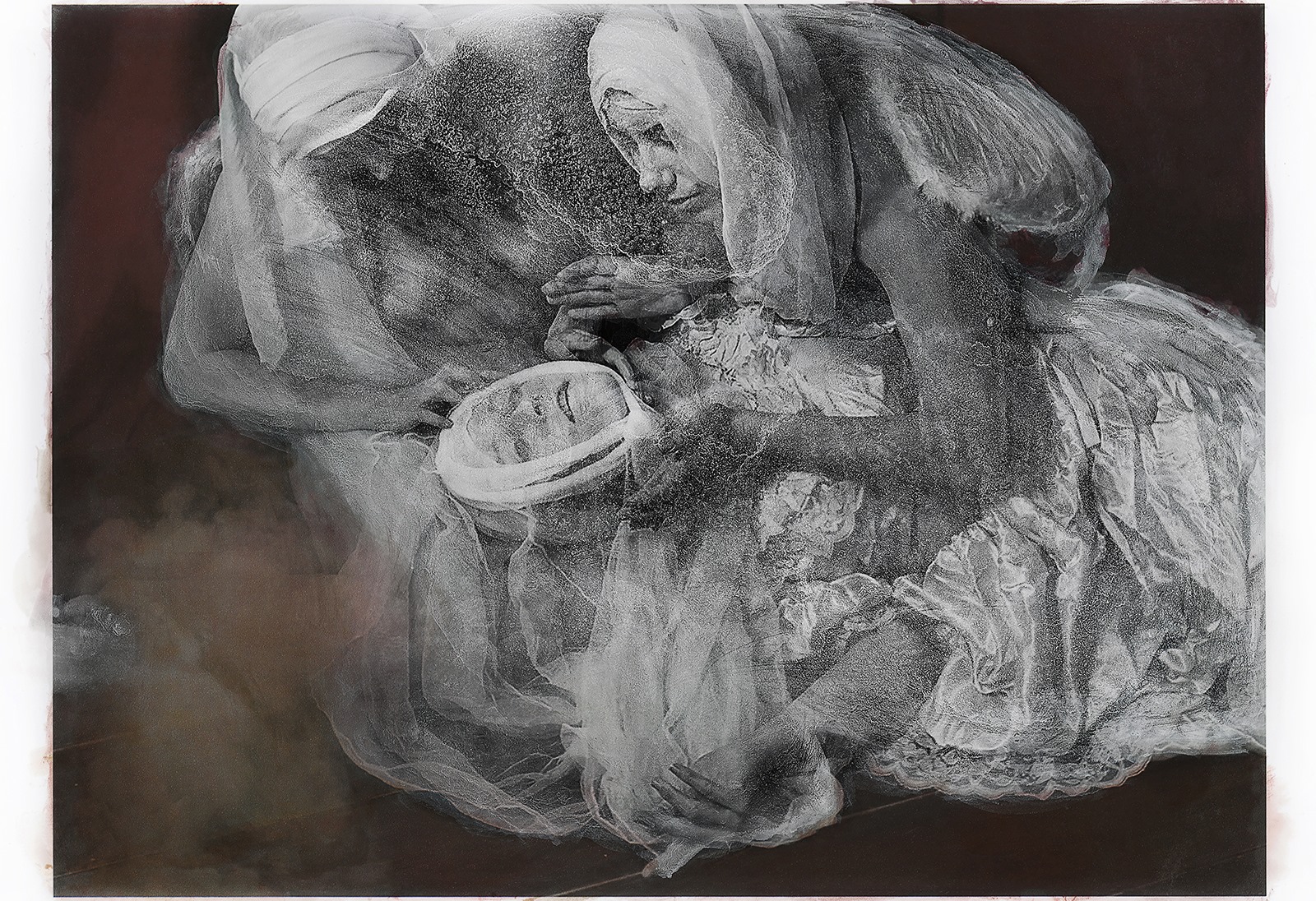

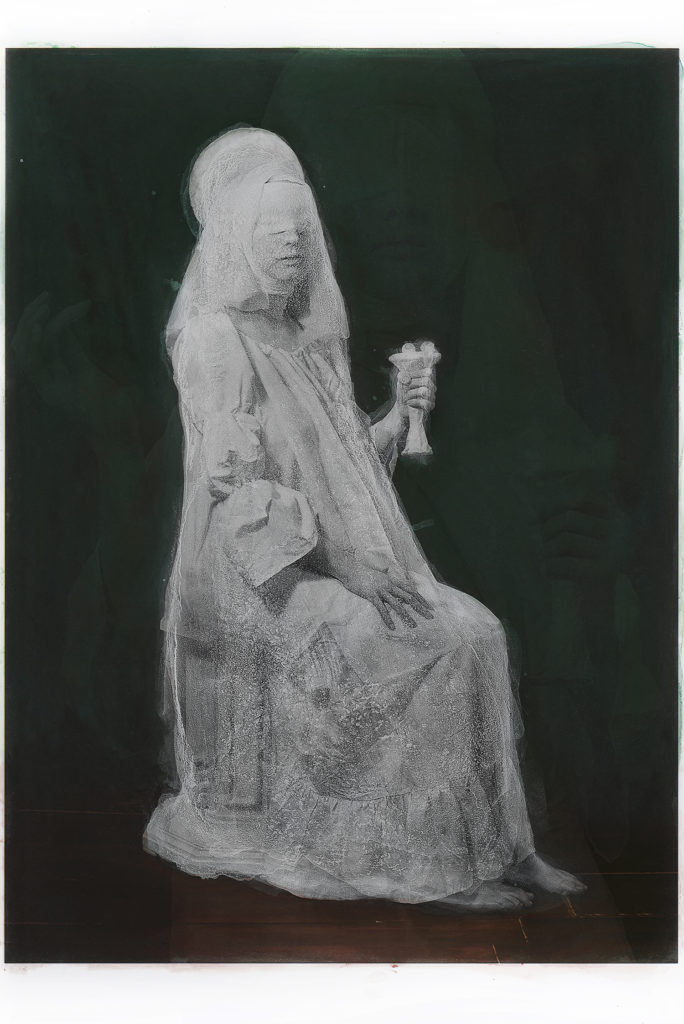

Brittany Markert’s daring introspective artwork resurrects the intimate, haptic process of analogue photography to create expressive, conceptual portraits encapsulating the spirit undergoing metamorphoses in photographic form, whilst at the same time freeing it and exorcising inner demons through cathartic expression. Rooted in Jungian psychoanalytic concepts, her visual narrative explores the repression of fears, repulsion and desires, the figure of the double, the polarities of the psyche, whilst everything is shown through a complex female gaze. Brittany’s art is of an unsettling yet alluring nature, as her visceral depictions of intense states of mind have the power of both enticing and terrifying the viewer. Her project, “In rooms” is a symbolic mnemonic device, a place carrying echoes of her psychological journey, a way of fulfilling the process of shadow work, and ultimately, a mirror in which each viewer sees whatever resonates with them the most.

DM: Your captivating visual diary is constructed from conceptual portraits and self-portraits, exploring sexuality, identity, mortality, and emotional states. Would you like to walk us through your emotional or psychological journey and the intimate meaning of the symbolism so evocatively and artistically portrayed in your photographs?

BM: In the back of my books are the words “For all the words I could never write, the camera became my pen”. Each year that passes by deeper layers of the unconscious are unraveled and frozen in a glass display for all to dissect, question and process. To walk through my emotional and psychological journey with my photographs is to view my books, Volume I, II and beyond. I have laid out my work over four years chronologically, in the spirit of a personal diary. It’s up to each viewer to find meaning, to find their own psychological journey between these pages.

DM: Can you reveal the steps you take on the path to artistic completion, from concept to the final versions of your creations?

BM: Ideas come when I least expect it and begin as notes or poor sketches in my journal. Sometimes it takes years or just a few days for me to attempt bringing it to life through my camera. Typically from there I wait at least a month to develop the film. I find this important so I am emotionally detached and can view the work with fresh eyes. It’s easy to like something because it’s new, but will it stand the test of time? Receiving the processed film and contact sheets is another step. Sometimes it’s quick and I see something profound, I print it and scan the final print into my archive for my books or website. Most often it’s slow, it can take 6 months to a year or longer to finally print an image. After printing in the darkroom, it takes a day to dry the paper, a day to hot press and more to press flat. My process is incredibly slow, a good year is getting 5-15 different great images.

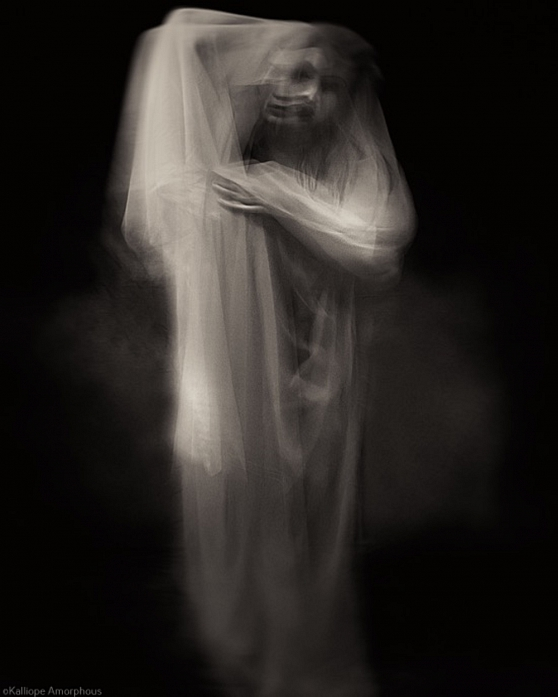

DM: The doubling and the multiple exposure effects frequently appear in your visual narrative. In one of your photographs, this aspect embodies a nightmarish trait, and appears to evoke an emotional metamorphosis, an embodiment of anguish. The elusive double seems to be linked with visceral agony and suicide in several instances. We also see multiple versions of the same woman, watching herself, whilst another photographic setting is reminiscent of Victorian spirit photography. What were your thoughts behind the dissociative nature of your stories and would you link it to a state of psychological disintegration?

BM: To recognize the polarities within ourselves and not accept either as the truth is to be free. This Jungian concept, the tension of the opposites, appears in my double exposures, at first unintentionally, and now with more awareness. Psychologically, Jung considers this the divine drama, we are always at battle with two distinct oppositions. Becoming aware of these polarities is the first step in the path to healing and enlightenment. My piece ‘Ode to Depression’ , a double exposed print of a woman asleep while another version of herself stands upright with a noose, is a familiar polarity capturing a part of my own and society’s battle with depression and mental health. Recognizing the innocent bystander asleep in my mind while the other begs to leave this world has saved my life. I’ve never been interested in documenting the reality of the outside world, I’m taking a microscope to the inside of the mind, the collective unconscious. The ghost like world of double and triple exposures mirrors this experience.

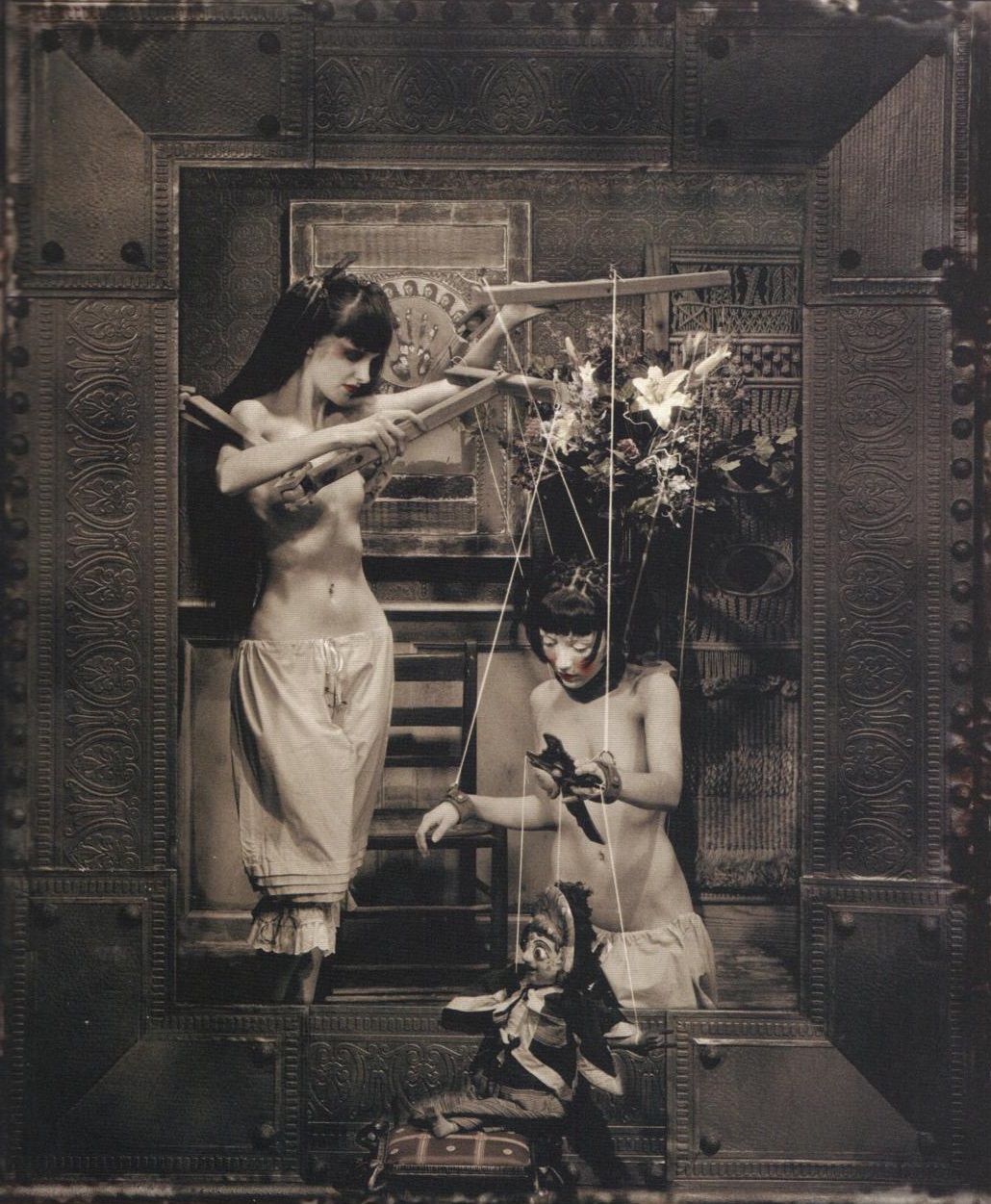

DM: Death and sexuality appear to be the dominant themes in your visual diary. There is a beautiful mix between fine art photography and visual erotica elements in your work, and in some ways, sexuality seems to be symbolically linked to death. The sexual activities seem “unconventional” and depicted through power plays. Would you like to elaborate on the themes of sexuality and power, as well as the link with death?

BM: Both sex and death are an intense physical release from life, a build up and movement of energy and the body. I don’t like to say what my work is or isn’t because ultimately it’s up to the viewer to decide, but I don’t see my work as sexual or physical per se, it’s more about the internal dialogue and tension within the mind.

DM: Has your photographic diary enhanced the intimacy and connection you already shared with the other models represented?

BM: To be seen deeply, and loved for the spirit you possess on the inside is a beautiful rare connection. The subjects in my work are typically lovers, close friends or kindred spirits. Sometimes this is the result of working together, or in most of the cases the work is a result of our close relationship. There is something incredibly intense and cathartic about creating the work In Rooms. Speaking from my recent 16mm endeavors, the subjects I have worked with have a type of familial connection. The exchange of creating the work this intentionally and intensely somehow bonded us by spirit, or at least me to them, but as close as this connection can be there is an equal and opposing force that also happens when I create my work. Some people are terrified of being seen deeply, so raw and vulnerably. I have experienced both the euphoria of life long relationships that feel like chosen family and the extreme sadness of connections that end abruptly because of the process of my work.

DM: You mentioned Anaïs Nin, iconic writer of erotica, as a source of inspiration on your website. What do you like the most about her work?

BM: The mention of Anais Nin in my artist statement refers to her personal diaries. She published Volumes of her life in chronological work and in the same manner I am publishing surreal diaries, in numbered volumes, in chronological order. There was a period, from 2012-2014 in which her writing became a mirror to my emotions and fed into my deep desires. The palpable lust and madness I felt reading her work revealed itself into my photography work, as have many other artists and writers over the years.

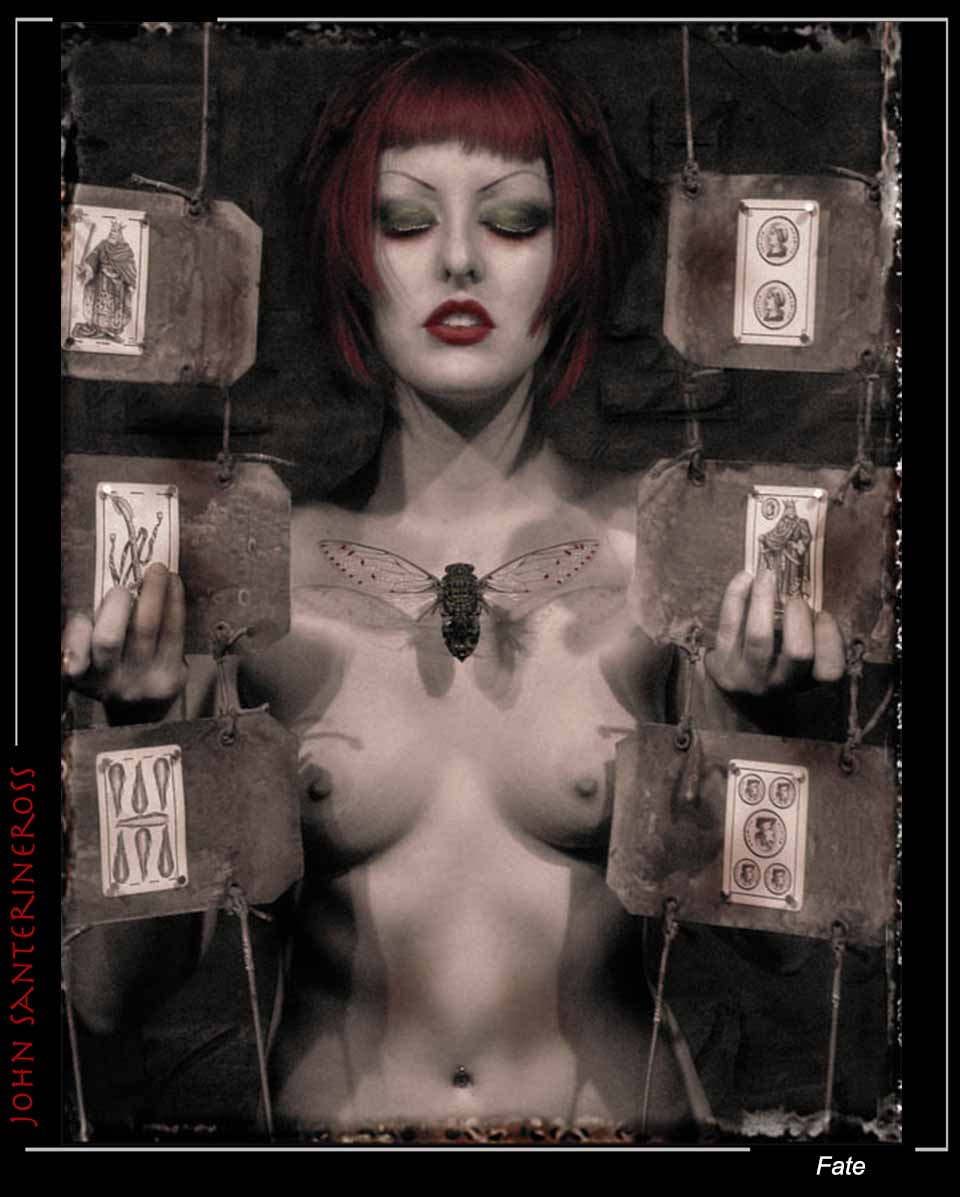

DM: What words would you use to best capture the emotions at the core of In Rooms? Are these emotions significant,-or dominant, in your life and inner world and are they temporary and cathartically released / alleviated once you express them through art?

BM: At its core, In Rooms is a realm that exists in the dark matter of our unconscious. The emotions are heavy, dense, often linked to sadness, pain, internal anguish, torment, unrequited desire and love. There are equal and opposing forces of repulsion and desire, for as much as one is seduced into the image, there is something unsettling pushing you back out. Although I live in a colorful house full of beauty and I see beauty everywhere around me, I’ve never been interested in making art about shallow or ephemeral feelings. The spirit of In Rooms is much like the gasp of air one takes before they plunge into the dark depths of waters unknown. It’s not that these feelings dominate my life, surely at times they do, but they are the ones that need to be released cathartically In Rooms.

DM: Your photographic stories unfold as intimate moments depicting human beings who beautifully connect with their vulnerabilities. In what ways did you tap into your vulnerability and the vulnerabilities of your subjects in order to fulfil your creative vision?

BM: The mind and the psychological landscapes that determine behaviors, reactions and emotions drive much of my curiosity. When I am in front of the camera, I show up with complete awareness and intention to the moment and I can only create meaningful work with others that I understand as deeply or that understand the decisive moment of creating as deeply. This takes time and what I call ‘perfect alignment’. A lot of the work involving mental health is created with close friends in which a part of our connection is to speak candidly about our mental health and suicidal ideation. The work I create about eroticism is with friends that speak candidly about their own dreams, fantasies and aspirations. I can not create work that doesn’t exist. If I attempt to force ideas or concepts onto people that don’t connect than it doesn’t work, the results will feel fake. There is fake art and photography everywhere, it’s exhausting as a highly sensitive person. I wanted to create a space for people to run to when they need to feel things vulnerably, when they wanted to be seen for who they are, not for what people think they are on the outside.

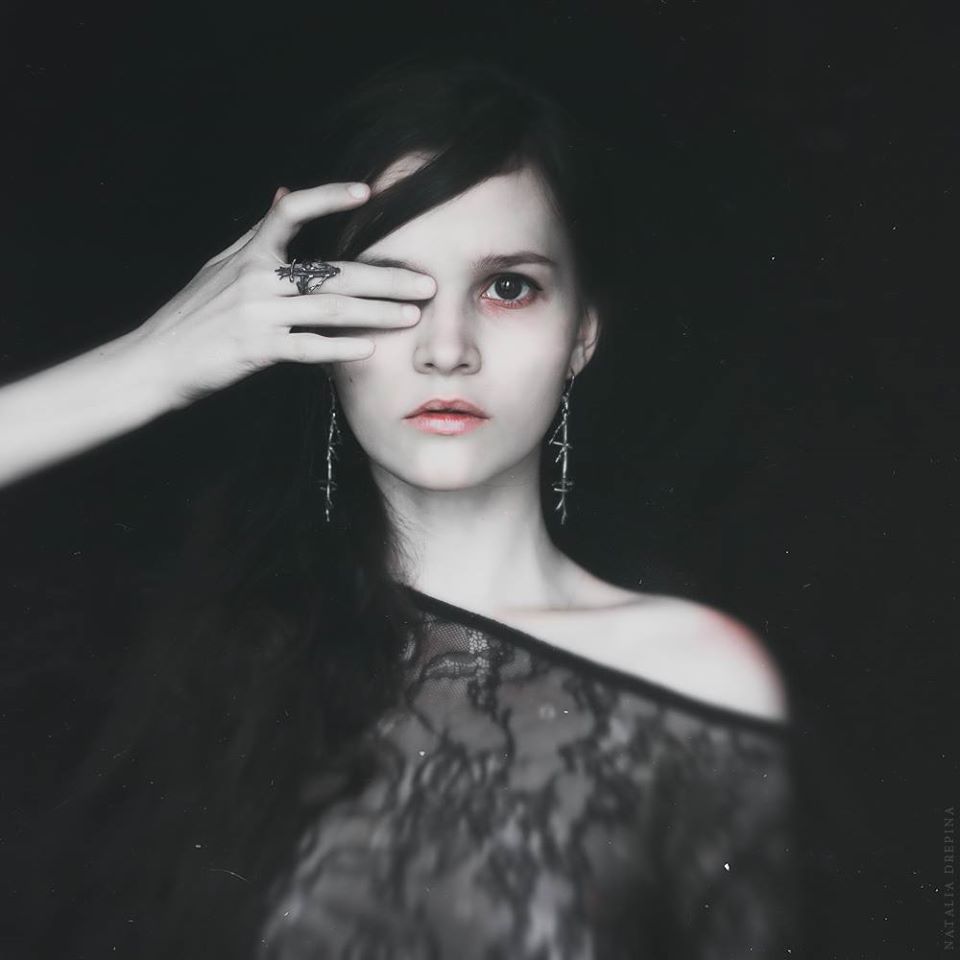

DM: At the same time, although in your work, the subjects’ nude bodies are on display- an act which is often seen as a way of relinquishing all inhibitions and fully ‘revealing’ your raw self, they are still sort of wrapped in or protected by an aura of mystery, by the unknown and so many things that are left unrevealed. Photography generally both reveals and conceals. Your photographs, however, seem to reveal a lot more whilst also concealing. The nudity is shown in artistic context, and the context is quite dreamlike, rooted in the unconscious mind. In contemporary society, it seems that posing naked is far from being the most daring form of uninhibited behaviour; revealing your true self emotionally and psychologically, unapologetically, and stripping off the layers of social disguise and conditioning is much rarer these days. As someone who is open to both ways of self-expression, is it challenging to reveal your self, to face your unconscious, to explore the darker impulses and desires of humanity, and to live a life of authenticity? Have you faced any unwarranted criticism for this?

BM: To enter the unconscious blindly, without information, is dangerous. One needs the protection of the ego and information to start the process of shadow work, of shining a light on personal and societal demons. Many of my mentors died by suicide. I went in blindly and spent years dictated by my suicidal ideation, by week long spells of crying, not washing my hair. I killed myself over and over again in my work, but that meant that I was still here in real life. I don’t wish anyone else this torment or pain, but my photographs and the process of making them saved my life. After this time I spent a lot of time researching jungian principles, psychotherapy treatments, memoirs by others with mental health disorders. This gave me protection and the ability to understand my work and actions on a deeper level. In becoming self aware I am over the hill of being blind to my unconscious and fear. The pull of suicidal ideation no longer wanes on me. It’s a miracle.

I’m lucky to not receive unwarranted criticism of my work, the people that don’t see the light in my work stay away and it seems hold their tongues. I would say, however, that I’m misunderstood frequently and judged, but this is a part of projection and entering a realm of shadows. My work becomes a mirror to many others’ suffering, pain and vulnerability and it’s unfortunate to be seen as the face in the mirror instead of their own.

When you’re coming into life and adulthood in your early twenties there is a thrill of being naked. This act of rebellion is less interesting now, but I am still pulled by the power and beauty of the human form. The most daring progressive thing you can do is to become self aware, create vulnerably and follow a path of enlightenment. Being naked is easy, it’s pleasing, but screaming vulnerably into the void while your soul and flesh drip blood of society’s torments is the challenging poetry I choose to work at every day.

DM: Roland Barthes said “The photograph represents that subtle moment when, to tell the truth, I am neither subject nor object but a subject who feels he is becoming an object: I then experience a micro-version of death: I am truly becoming a spectre” (from Camera Lucida). When you are photographed, you get to see yourself as “other”, as something external, and you recognise yourself in and identify with this likeness, this photographic imitation- a specific, fragmented image in time, which is less than you. On the other hand, through self-portraits the lines between self and other, between subject and object, become blurred, as you become both. This artistic reconstruction of the self can induce a re-connection with and sense of control over your image, whereas in other contexts, seeing yourself as “other” or being externally objectified could potentially have the effect of destabilisation or alienation. Do you feel that your self-portraits have any effect on your self-image and identity, and do you ever internalise this way of seeing yourself – i.e. objectifying yourself – in your life?

BM: The camera has a way of revealing that which I cannot see clearly in real life, sometimes it slaps me in the face with its revelations. It is quite dull when I look in the mirror, but the world through my camera, In Rooms, has changed the way I know myself and others forever. At first, when I blindly dove into my unconscious and came out as distinct archetypes they had a way of seeping into my real life, of confusing my actions and relationships, at times even inducing a state of psychosis or depression. It can be immensely difficult to stay strong and centered when I confront my work, which is why I create so rarely. Of course the characters and the body are me, and reveal parts of my mind, but I am not the characters. This took a lot of work and healing to safely navigate how to create my work but not let the results and image of myself be my own detriment or fate. Sometimes I feel I am boxed in by In Rooms, that my image, my body or energy is supposed to align with the work but lately I’m learning to walk away from this, to exist outside and be at peace knowing the work is just a part of me, a truth but not the truth.

DM: You have modelled for other photographers before. From a model’s perspective, are self-portraits a more freeing and rewarding experience than portraits taken by others, since you are in charge of the ways in which you present and represent yourself and your individuality? Photographing yourself nude, in particular, does it come with a sense of liberation and does it make you get in touch with your sexuality more?

BM: The act of creating out of love is freeing, I find this to be true whether I am a model or the photographer. It is rare that everyone involved on a creative set is perfectly aligned, every one eager to breath life into a piece of art. I cherish these times even if I am just an assistant on set. Modeling for others is ultimately limiting, the roles I was cast as were repetitive and not challenging. Ultimately my journey with self portraiture has been more rewarding, a path of discovery, catharsis, and creativity. I have built a life for myself with my work and this would never happen with modeling.

To be comfortable in one’s skin is liberating, to see and feel nudity as being human, not being sexual, is also liberating. There is so much taboo growing up demonizing the body and sexuality. For years of my early adulthood my body was also at the liberty of other artists, mostly the male gaze and it was empowering to see myself in a way that was my own, to take back my own story. To be an artist and create is to feel everything deeply, this includes sexuality. To present oneself as both the creator and the object of desire is to also see how others desire you, it opens up a portal of sexual advances, flirtation, relationships, etc. For awhile I was free to discover, more so than ever before because of my art, but I have grown less interested in being nude for the sake of being nude or as an act of rebellion. When nudity does appear it is a sign of comfort, of curiosity, of beauty, of being human.

DM: Your photographic style is reminiscent of Francesca Woodman’s intimate self-portraits due to the nudity depicted in black and white analogue portraits, the visual exploration of the relationship between body and space, matters of identity, and the nude female body appearing like a ghostly, elusive presence in confined spaces. The more provocative aspect summons up Nobuyoshi Araki’s depictions, interpreted through the female gaze and given a surrealist turn, and the atmosphere and aesthetic also carry echoes of Repulsion (1965). Do any of these references resonate with you in some way, or what are some sources of inspiration for your project besides Anaïs Nin?

BM: It’s mentioned in my artist bio that my work is ‘from the school of Francesca Woodman & Duane Michals. Woodman’s work became a mirror to my own feelings and understanding of the world, her work opened a door for me to believe it was possible to write my own story. I began my work at an age she never reached, in many ways I consider my project a way to keep her journey alive. There are many artists and people I owe considerably thanks to: Diane Arbus, Vivian Maier, Claude Cahun, Joel Peter Witkin, Hans Bellmer, Maya Deren, Carl Jung, Francis Bacon, Lauren Simonutti, David Lynch, Stanley Kubrick, Catherine Robbe Grillet, The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Sarah Kane, to name a few. I can’t say Araki or Repulsion had any influence or effect on my work, but I am trying to represent the female experience on genres of work that are typically accredited to men. It is frustrating that the ‘female gaze’ in photography is often delicate, sad, vulnerably with muted colors and pink. I don’t recognize myself through this lens, In Rooms is bold, intense, heavy. The gender in many cases is androgynous. In Rooms presents a gaze I couldn’t find anywhere else when I was looking for comfort, for friendships, for a place to call home in the real world, so I created my own.

DM: Talk to us about your fondness for analogue photography, whether you ever tried shooting digital, and why the latter doesn’t appeal to you as much.

BM: Lately, especially with the younger generations pull towards Tik Tok, phone apps and lack of education of the darkroom, I feel the world of analogue slipping away like sand between my fingers. It’s disheartening that the film aesthetic is more easily achieved with a few clicks of a button on a phone, but I believe so passionately in the tradition, in keeping the craft alive and physically involving my entire being in the process of creation. To touch a silver gelatin print and feel the energy of the process is something I have yet to see achieved with any digital image or print. There is a lack of connection, a lack of tenderness, between a human and a digital device. Analogue serves as a medium of the human soul, of humanity. It does not hinder the connection, but enhances it with each step, from physically building the set, cranking the film and watching the image come to life while one’s finger tips hold it wet in the developer. The entire process is profound, challenging, infuriating, and absolutely euphoric. I’d say it’s love, it is a gift, and I have zero desire to put anything, such as a digital device, that may hinder my ability to connect to humanity or communicate the inner world I feel so palpably.

DM: A photograph can be a mnemonic device and an extension of identity, but it can also have the effect of erasing the past and replacing it with an image or making your memory revolve around a particular moment or representation. There is an element of absence in any photograph: what comes before the shot, what comes after, the thoughts of the subjects, identities, and perhaps the emotions that bind people together are potentially “erased” or disguised. Your photographic project, especially since it partly features people you love, can also constitute a recording of the past. The way you represent it is symbolic, stylised, at times surreal, with an oneiric quality. To what extent do you feel your visual diary has protected memories and to what extent has it disguised or distorted your memory or your autobiographic narrative?

BM: To the extent that my work is autobiographical, it is my hope that the work is equally documenting a collective psychological experience so that when people view my work, they feel and experience their own story. I never see my photographs for what they are, as you mentioned, I see the time in my life they were created, I feel my emotional journey leading up to that point, I see the people in my life that time. The work becomes a mirror to our current times and I forgot how I created it in the first place.

In Rooms is a delicately laced web of my memories, a graveyard of love, of torment, of deep healing. I visit it to feel at peace, to thank it for guiding me to a more honest place. It protects me from the boredom and pain of reality, and presents the essence of life that is constantly changing. In Rooms is a riddle that even I can never figure out and I can only hope it continues to inspire and heal myself and others.

To support Brittany’s work and view behind the scenes, darkroom and creative processes subscribe to

patreon.com/inrooms and gain access to her private instagram account and print discounts

To purchase prints, books, postcards or rent her films visit www.InRoomsGallery.com

To view galleries of Brittany’s work visit www.In-Rooms.com

Instagram: in_rooms