Collage constitutes a dynamic medium where elements of the familiar are unsettlingly displaced into unfamiliar territories, offering a visceral exploration of the uncanny. Teetering between the comfort of recognition and the chilling thrill of the unexpected, the realm of contemporary collage art opens up a world of paradoxes, where the mundane is rendemasred extraordinary and the predictable unexpectedly disrupted. Among the artists shaping the narratives in this sphere in the virtual space, Angelica Paez, Colette Saint Yves, Sato Masahiro, Sara Shakeel, and Robin Isely each stand out with a distinct approach to this medium, employing their unique artistic vernacular to translate the ethereal, the uncanny, and the nostalgic into tangible, visual experiences. As we shall see, these contemporary collage artists, albeit divergent in their techniques and thematic focal points, share a predilection for the provocative interplay of reality and unreality.

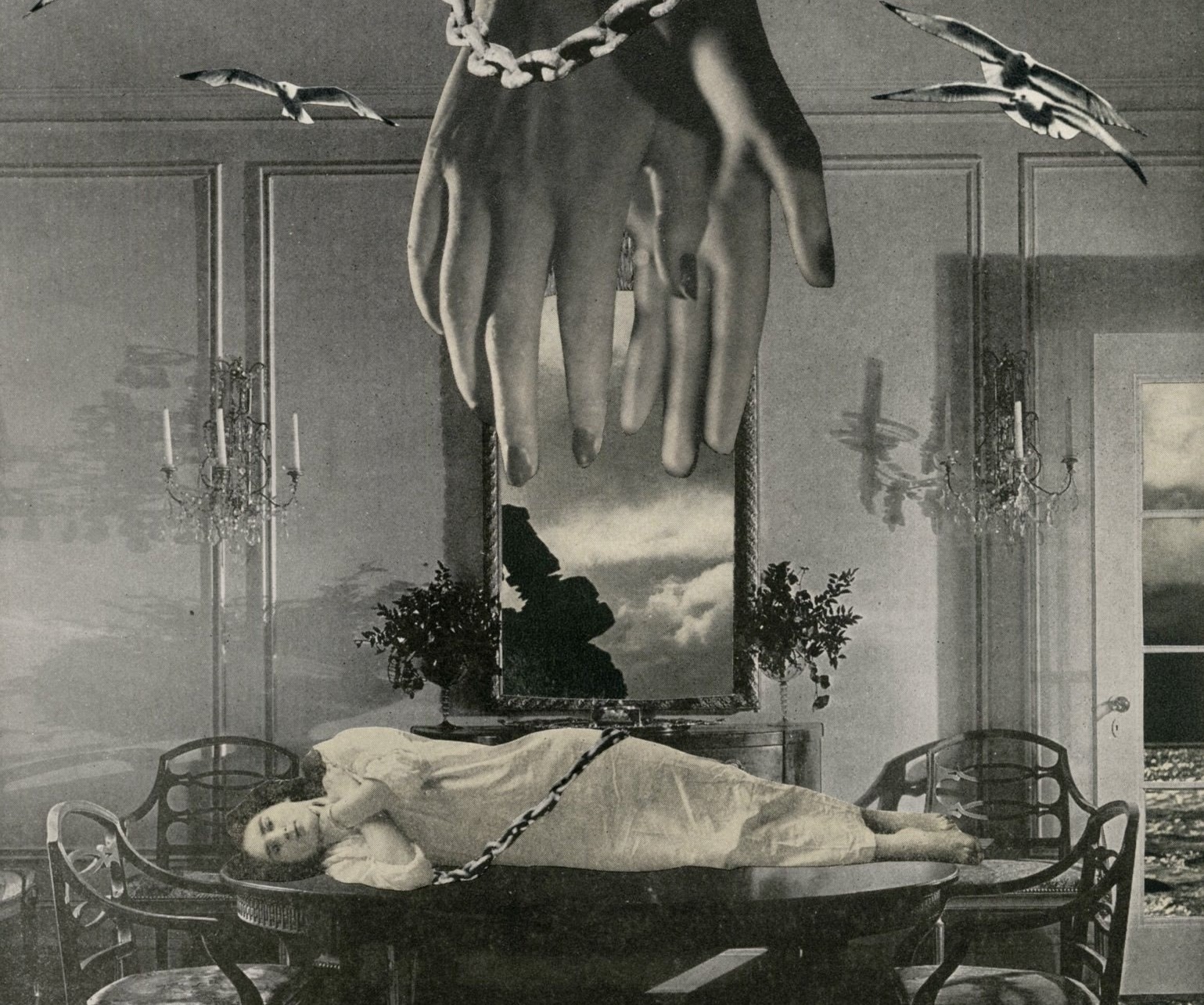

Angelica Paez‘s surreal monochrome collages engage our perception in a ludic, nostalgia-infused dialogue of complex, dreamlike contradictions through the depiction of hypnotic scenes created by cutting out old papers, catalogues, and magazines collected from second hand markets. The eerie atmosphere of her work is achieved by incorporating familiar objects in strange ways in intimate settings, unveiling images embedded in the unconscious. These enigmatic scenes, often characterised by a cleverly conceived atmospheric eeriness, artfully compel the viewer in a way that simultaneously challenges and delights.

Paez’s strikingly enticing works echo her early love for collage-making, a practice she developed from a tender age with safety scissors and her mother’s discarded magazines. Today, her notable artistic skills, manifested in her ability to conjure complex, layered narratives, reveal a sophisticated metamorphosis of her childhood pastime, though her affinity for the tangible, tactile process remains undiminished. Her intricate compositions, often bearing the inscription “Houston, Texas”, hint at the subtle interplay between the origin of her eclectic materials and their ultimate reincarnation within her art, further accentuating the intimate dialogue between the past and the present, the mundane and the extraordinary that permeates her nostalgic oeuvre.

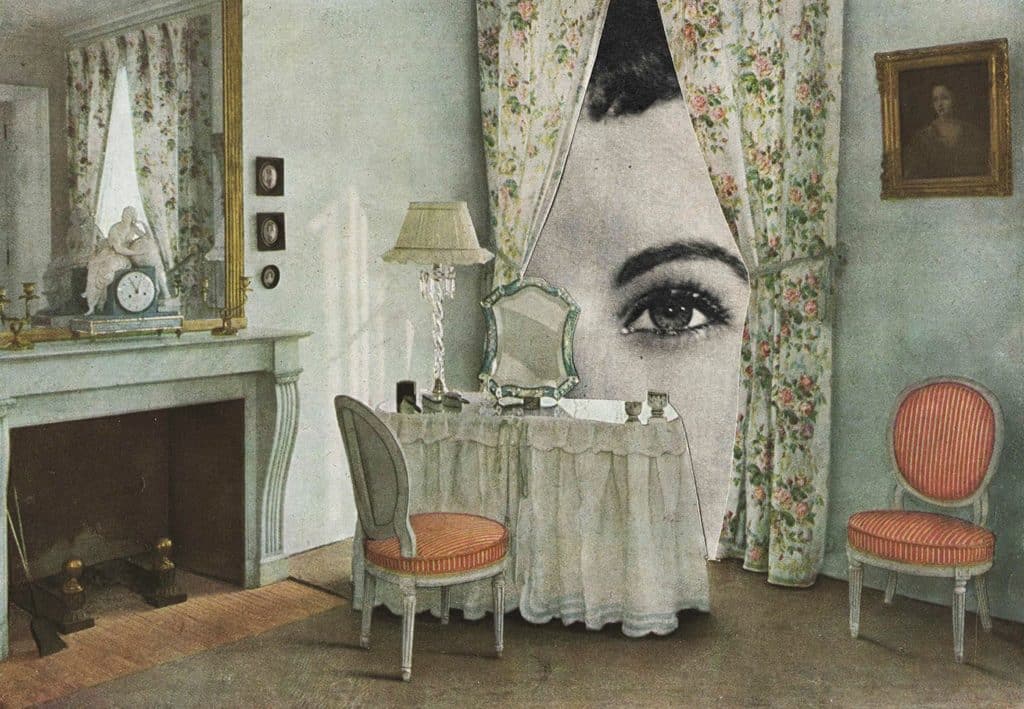

Colette Saint Yves is a photographer and collector of evocative imagery featuring film stars with enigmatic gazes, mysterious apparitions, celestial settings, and melancholic monochrome nature shot in analogue. The artist creates haunting, surreal collage art by interweaving a range of elements from photographs, films, and books to create dreamlike, at times unsettling scenes that intrigue. Her work also acts as a bridge that connects modern audiences to the vintage aesthetics and poignant emotiveness of silent cinema. Saint Yves’s distinctive methodology involves the meticulous collection and curation of varied visual artifacts – abandoned photographs, vintage postcards, enigmatic screencaps, and illustrations from time-worn, antiquated books. These become the eclectic building blocks of her captivating collages, providing a rich, layered, and textured backdrop for her surreal, dreamlike compositions.

Her evocative works usually exude a deep sense of melancholy, offset by the mysterious, irresistible allure of the subjects she artfully depicts, often incorporating elements from celestial bodies and the untamed natural world. The striking monochromatic tones frequently featured in her intriguing collages heighten the overall enigma and ethereal, otherworldly nature of her mesmerising compositions. Each intricate piece is an exploration into the depths of the subconscious, where evocative nostalgia and vivid fantasy intertwine, eliciting a memorable sense of intrigue and a poignant longing for an elusive era irrevocably lost to time.

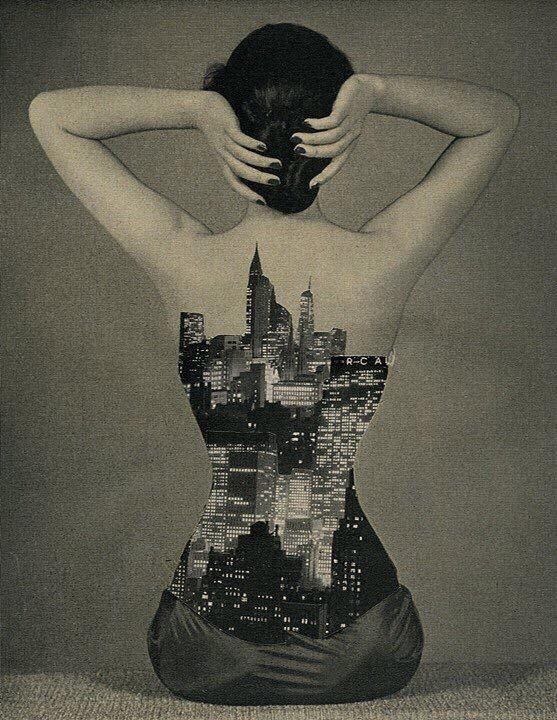

Sato Masahiro, operating under the creative pseudonym Q-TA, is a distinguished collage artist residing in Tokyo. Q-TA’s works consist of an innovative fusion of ephemera from antiquated encyclopedias, exploiting both digital manipulation and traditional techniques. The blend of old and new characterises his strikingly surreal artistic style. Masterfully employing both digital and analog techniques, he invites the viewer into compellingly strange and aesthetically rich landscapes through a juxtaposition of elements into an improbable assembly generating dreamlike, surreal compositions. The ability to render the absurd into harmonious continuity forms the distinctive appeal of his body of work.

In one if his interviews, Q-TA mentioned his hopes for audiences to experience a mix of feelings reminiscent of childhood book reading—surprise, delight, and a nostalgic yearning. This child-centric approach is not merely aesthetic; it underscores his aspiration to convey an innovative perspective by bestowing upon his audience a glimpse into a child’s world, whilst situating children in these distinctive, surreal environments. Even though his works don’t carry explicit messages, they are embedded with fragmented keywords, adding layers of subtle commentary and sparking curiosity.

Imbued with a profound understanding of the interplay between human form and animalistic instinct, San Francisco-based digital artist Robin Isely eerily bridges diverse historical and aesthetic influences in his haunting, compelling collage work. His compositions, marked by an uncanny fusion of the sublime and the unsettling, draw from a broad palette of eras and stylistic movements – the grandeur of classical mythology, the intricate mysticism of the Gothic period, the allure of French New Wave cinema, and the visceral expressiveness of the tumultuous sixties.

Isely’s intriguing, surreal collage art, resonating with a dreamy and sometimes disconcerting quality, crafts immersive, eerie yet aesthetically pleasing visual narratives. Through a creative blend of vintage photographs, his work constructs uncanny, richly textured scenes that immerse spectators into a universe where reality and fantasy seamlessly intersect. The effect is an enchanting, eerie tableau that invites a journey into the labyrinth of the subconscious, stirring up nostalgia and discomfort in equal measure.

Recognised for her distinctive combination of traditional craft techniques and experimental practices, Jana Sojka is a self-taught mixed media artist creating haunting, evocative art which often features natural motifs, fragmented words, vintage textures, and self-portraits. Born in Poland and now based in Bristol, Sojka’s varied yet recognisable body of work reflects her life journey and her intimate connection with the world around her. Having begun her artistic journey through a fascination with photography, Sojka soon started to explore various mediums, incorporating collage, animation, and journaling into her creative process. The result is a distinctive, multifaceted oeuvre that bridges the gap between introspection and universal resonance, personal memories and shared narratives. One of the signature elements of Sojka’s work is her dedication to using traditional craft-based techniques and materials. Sourced from her family home, old ephemera play a central role in her collages and prints, grounding her creations in a tangible sense of history and continuity. She imbues these pieces with a nostalgic resonance that is both deeply personal and universally relatable.

Sojka’s work also displays a profound connection with nature, a theme that is often manifested in the presence of floral motifs and her exploration of natural light and shadows. Her nighttime escapades, as she calls them, led to a fascination with the interplay of darkness and light, an element she beautifully translates into her photographs and animations. Her artistic practice is guided by intuition and emotion, evident in her ‘always experimental’ approach. She believes in the importance of surrendering to creative impulses and the process of making art as an act of liberation. This philosophy permeates Sojka’s work, resulting in pieces that encapsulate the raw and authentic beauty of life. Within her oeuvre, Jana Sojka’s journals hold a special place. They are collections of thoughts, images, and ephemera, each telling a different story. They constitute both a documentation of her life and a channel for processing feelings, an intimate reflection of her journey that she occasionally shares with the world.

Sara Shakeel, the original crystal artist and a former dentist from Pakistan who found her artistic calling in the gleam and glitter of crystals, creates scintillating, bedazzled collage artworks. Through her striking, glamorous art, various aspects of the world are imbued with her signature magic. The magic is created by adding layers of crystals and glitter to subjects ranging from pop culture and artists, classical paintings and religious iconography, urban aesthetics, luxury brands, fashion, as well as tears and stretch marks promoting body positivity. Her artworks blend a sense of healing, empowerment, and joy with a unique aesthetic that draws the viewer into a universe studded with shimmering details. Shakeel uses her art as a medium of personal therapy, each creation reflecting a therapeutic journey that resonates with viewers and triggers a sense of shared healing.

Despite not having any formal training, Shakeel’s rise to fame, courtesy of social media platforms, has seen her distinct aesthetic reach over a million followers. Her first body of work, notably known as #glitterstretchmarks, challenges societal norms regarding body image. It reflects her stance towards body positivity, as she embellishes images of stretch marks with gold glitter and crystals, transmuting perceived imperfections into vibrant art. This theme, along with the artist’s penchant for incorporating celestial galaxies into her work, underscores her talent for finding and creating beauty and strength in the most unexpected places. What sets Shakeel’s work apart is not just her stunning technique but also the emotional depth and vivid storytelling that unfolds in each creation. Drawing inspiration from her surroundings, memories, and personal desires, she uses her pieces to communicate complex emotions through dazzlingly bright and captivating crystals.