Netflix’s The OA, created by Brit Marling & Zal Batmanglij, is an intriguing, engrossing fantasy show centred around Prairie (played by Brit), a young vanishing woman who resurfaces 7 years after her bizarre disappearance, to the happiness and bewilderment of her adoptive parents. After her peculiar return, she refers to herself as the OA and focuses on her mission to save other captives. The OA enrols a group of school misfits and their teacher on a mystical mission, meeting them at night in an empty house in a cult-like gathering. The narrative of her unusual life and disappearance unfolds, a fragment per night, through her spellbinding storytelling. Starting from her fairy tale-like description of her Russian roots, her story features near-death experiences, travels within memories, dreams, and across parallel realities, celestial guardians, a scientist with an unrelenting obsession and thirst for knowledge, a group of special people trapped in a glass cage and bound by uncanny experiences, a soulmate connection, and transcendental ritualistic movements that open up invisible portals to different worlds.

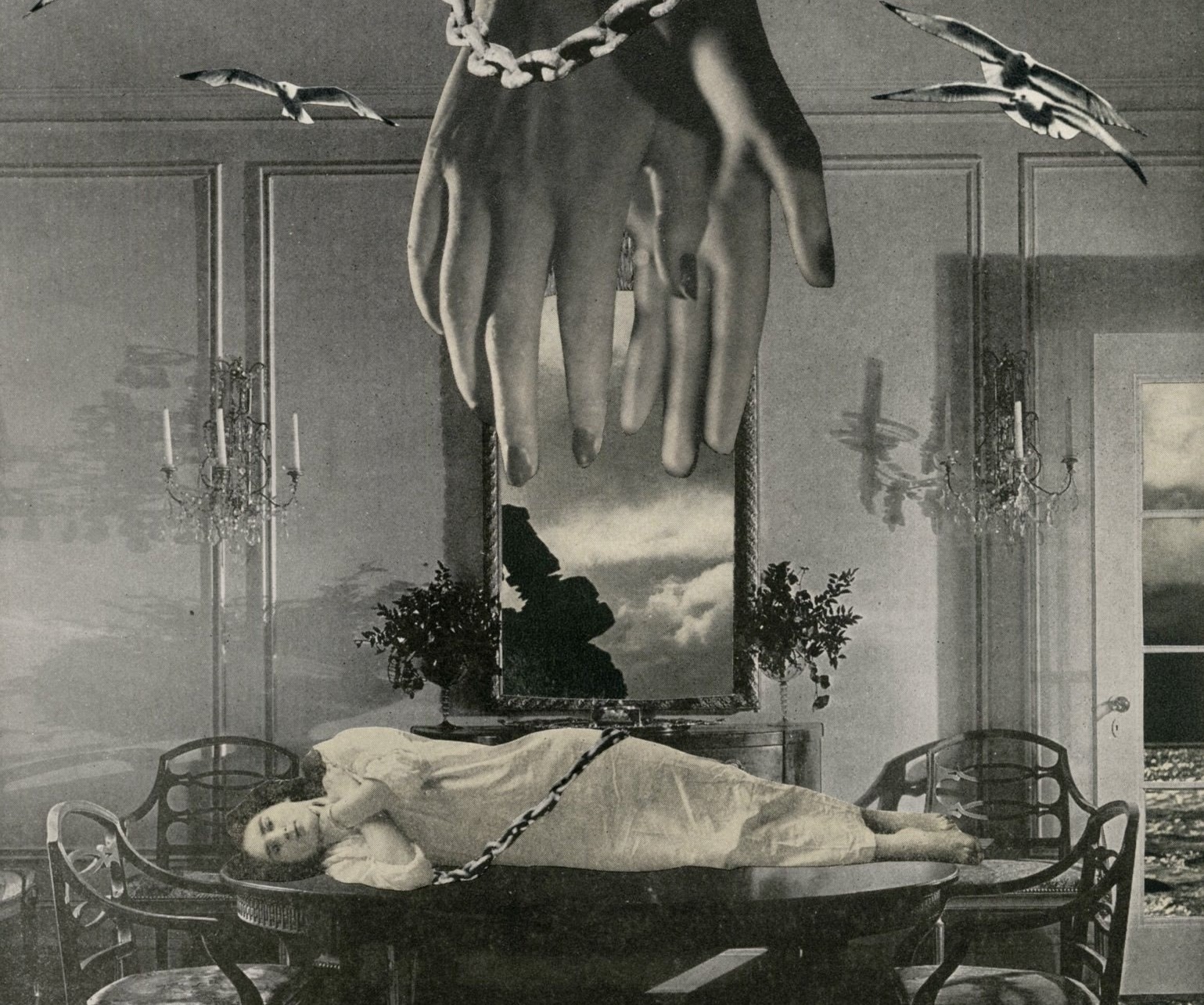

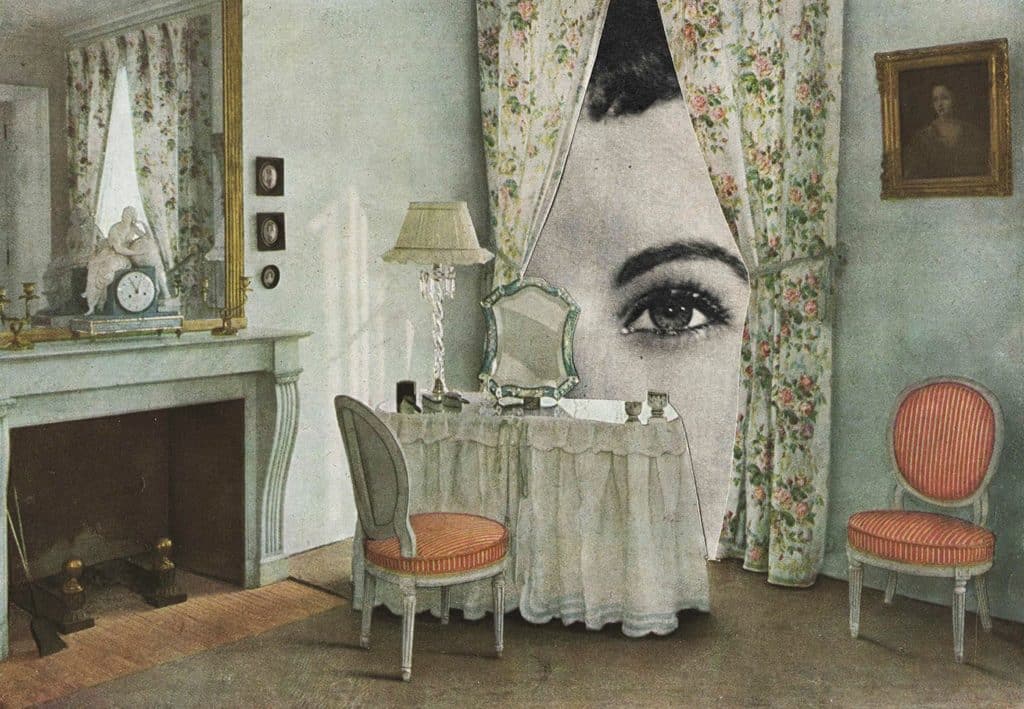

The show takes us on an enchanting journey with striking surreal visuals, endearing characters, and evocative meditations on life, connection, identity, fear, entrapment, and freedom. Supernatural motifs are interlaced with sci-fi theories of parallel worlds, as the show stimulates our minds to contemplate the concept of multiple realities whilst grasping the design and nature of the complex OA world in rapture and being immersed into fantasy. The OA, born Nina Azarova, the daughter of a Russian oligarch, spends the first years of her childhood with her father in a lonely mansion on Russian land, where she is often plagued by vivid nightmares- some of which turn out to be premonitions. One of her foreshadowing dreams is that of being submerged in a huge aquarium, where her senses are heightened and she is drowning, unable to get out. In order to help get her rid of the nightmare, her father teaches her a lesson about bravery, taking her to a frozen lake where she submerges her body into the ice-cold water, to conquer her fear. Water is an evocative element in the story, connected to memories, dreams, and visions; it’s also a way through which parallel worlds echo each other. It evokes the fluidity of passing through worlds, through selves. Water also symbolises duality – creation and apocalypse, death and rebirth. This is relevant to the series- there are many striking scenes in which water is associated with the sinister, with something beautiful, as well as with the uncanny. Nina’s underwater dream prepares her for the traumatic turning point in her life, her near-death experience, that propels her into a celestial plane of existence. She awakens in a surreal diaphanous setting, where she meets the archetypal wise old woman for the first time- the one associated with choices, sacrifice, and cryptic discourses about the OA’s life trajectory. Nina wakes up blind and a series of events quickly follows- she is relocated to America, her father dies, she is adopted by the elderly couple. Many years later, unconvinced that her biological father is dead, Nina, now known as Prairie, spends her days playing the beautifully transfixing violin song from her childhood in a place where she thinks he might hear it, in hopes of a reunion. “The biggest mistake I made was thinking that if I cast a beautiful net I’d catch only beautiful things.”, she says. Instead of her father, another man is lured by her tune- her captor, Hap, whom she initially views as a father figure,as being “strong, smart, uncompromised”, following him blindly right into his trap. This marks the beginning of the experience that was going to re-shape her life.

Hap (Jason Isaacs), the mad scientist of the series, is initially obsessed with studying near-death experiences, seeking to revolutionise science- to pierce the deeper truth by examining paradigm-shifting phenomena through inhumane experiments. At first he exhibits a conscience and feelings of guilt, remorse, and attachment, as well as making rather hollow claims that he thinks of his captives as collaborators; however, his already faint moral compass dissipates by the end. He remains fond of the OA throughout the whole series, hoping that in the next world she will forget his horrible acts, but his nature never changes. As the OA repeatedly points out, his gruesome secret inevitably projects him into a life of loneliness, his version of power being built upon violence, imprisonment, and dread. He has one other scientist “friend” he can bring up the subject of his experiments to and, during their talk, Hap turns out to be more human compared to his cold-blooded conversation partner. The latter is psychopathically at peace with his ruthless macabre ways, saying “Here’s the terrible, beautiful truth. No one cares. There is no line between good and evil. There is only what a man can stand.” Their motivations also diverge: whereas his rival is driven by financial greed, Hap wants to figure out the truth for himself more than anything, “God, I want to taste the truth. I just wanna walk out of the dark.” In the second season, Hap’s interests evolve- he finds a grotesque method to build a map of the multiverse as a way to break limits and pick the destination of his future inter-dimensional travels rather than making risky leaps into the unknown.

The soul connection between the OA and her fellow inmate Homer is the most touching aspect of the series, holding the story together. They have been through a traumatic experience together for 7 years, confined within a glass prison with only some plants and a stream to touch and frequent encounters with death. When the OA/ Prairie arrives there, she is blind. He helps her acclimate, survive, and stay sane. When she describes her strange inter-dimensional excursions and unfathomable escape plan, giving him seemingly absurd instructions, he believes in her. They share their travels in death, their discoveries, and the arcane knowledge they gather from other dimensions. Both persevere in their mission and lift each other’s spirit. They dream of moving to another realm where they can finally be free and live together. Hap tries to pull them apart, by planting seeds of doubt about Homer and their plans- “You’ll always be the girl willing to risk everything for the chance to achieve something extraordinary. I know you, Prairie. He will never understand that about you.” Prairie remains unwavering in her beliefs and feelings. In the second season, however, their connection is challenged as Homer’s consciousness appears to be absent in the new world. His initial self has seemingly got lost somewhere along the way; actually, his consciousness is dormant within the mind of his alter ego, namely a psychiatry resident who became a big fan of “Hap” (Known as Dr Percy in the second world) after reading his book, “Quantum Psychotic”. The OA / Nina Azarova, now his patient, tries to reawaken his memories of their previous life together, whereas he sees her through a psychiatric lens, as a delusional individual with dissociative identity disorder. Eventually there are a couple of moments and gestures that act as a catalyst to revive Homer’s consciousness. Another inter-dimensional traveller that the OA crosses paths with, Elodie, mentions that Homer and the OA have a powerful bond that transcends multiple dimensions, but that their paths are doomed to be closely interlinked with Hap’s. Elodie suggests that a part of the OA- probably an unconscious part- wants to travel with Hap too. Hap might mirror a part of her shadow self, perhaps a thirst for knowledge and hunger for the extraordinary, or it might simply be that he is a reflection of her intense parallel life experience. An attempt to escape the echo of this cosmic family would shatter their identities and the OA’s connection with Homer, as it increases the risk of amnesia after their jump. “You could find yourself inside a life completely unrecognisable to you. Not to mention you and Homer might not even know yourselves in a dimension outside an echo.” In fact, the second season gets wrapped up by a glimpse into a metafictional third dimension where everything seems different and they are far away from the initial versions of themselves, thanks to Hap who somehow holds the reins of the jump for both of them. Knowing this, the OA urges Homer to come and find her in their new life and resurrect her memories, her “true self”.

The first season injects the idea of the unreliable delusional narrator towards the end, leaving us on a note of ambiguity, as there are no glimpses into another dimension beyond Prairie’s subjective recollections -contrary to our expectations throughout the show. The ending of this season might thus be perceived as anti-climactic. Although the journey is slow-paced, it works well as the OA (Original Angel) keeps you hypnotised like a modern ethereal Scheherazade. The second season- whilst still introducing the element of shared psychosis as it places the captives in a psychiatric clinic- is clearer about the nature of reality and the way it interprets the concept of multiverse in its world design. The second season is also more dynamic and dizzying, adding new layers of meaning, astral planes, and a variety of fantasy and sci-fi motifs to the story: the dream factory, where dreams are being recorded in order to detect patterns and collect premonitions, the haunted horror house re-interpreted within a sci-fi context, as a dangerous wormhole into parallel universes and timelines, the psychic, the mirror apparition, the spiritualist method of summoning someone from another dimension, the telepathic octopus, and the animist depiction of trees.

“Nina saw the whole world. But I saw underneath it.”

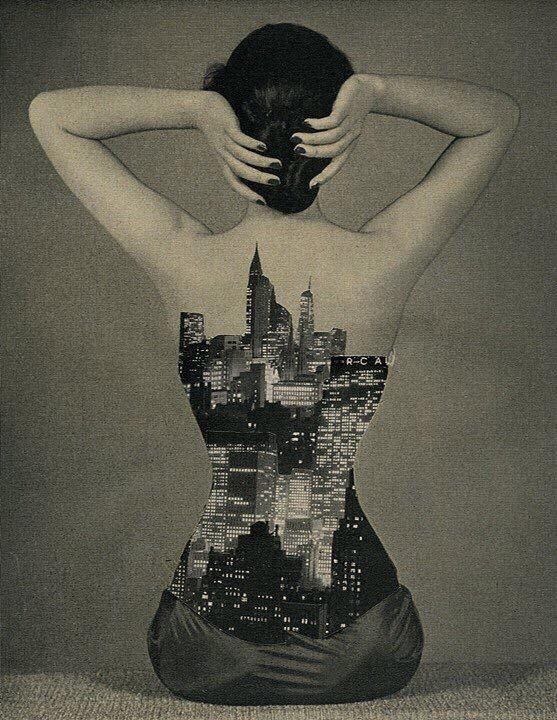

The second dimension is an alternative timeline in which Nina made a different choice during a key moment in her life, which propelled her to a completely different life path. She never got on the bus that crashed into water, which erased her previous thread of existence as she never went blind and regained her vision, never had a near-death experience; her other life being replaced with experiences that created another version of herself. This version has lived a luxurious, decadent, hedonistic existence with an abundance of privileges, money, drinks, earthly possessions, and boyfriends, away from hardship, and hasn’t acquired empirical experience of other worlds. She is a wealthy Russian heiress whose former partner runs a dream factory and created a VR game / puzzle for unethical crowdsourcing purposes, leading teenagers to a dangerous place in search of explanations for a peculiar phenomenon. When she finds out about what his project involves, they fight. Although the personalities and lives of Nina and Prairie are entirely different, they both gravitated towards the supernatural and the esoteric, to an enigmatic phenomenon, as parallel worlds leave echoes in others. When the OA enters her life, the discrepancy between the two of them is transparent; and the OA/Prairie doesn’t have access to Nina’s consciousness at first. When people travel to another world and inhabit a new body (with the same appearance), it seems they tend to either suppress the consciousness of their host (as most of the inter-dimensional travellers in the show do) or remain dormant if the consciousness of the body they entered does not seem to integrate the new consciousness. It’s not very clear why this happens – why Homer didn’t awaken from the beginning as his initial self and why the others did. The OA eventually frees Nina’s consciousness by facing her trauma- the moment that caused the split between the two parallel realities, generating the alternative timeline. It is implied that this process makes her integrate the consciousness of the other Nina and they merge into one.

Contemplative questions you might ask yourself:

The rules of inter-dimensional travels in the show are somewhat elusive and shifting. At first we are led to believe the characters have to become unconscious in order to travel somewhere else, but in the second season that doesn’t always seem to be necessary. How does that work and how does Elodie re-appear in the same timeline? What happened to her vessel? Why did the OA tell Homer to stay alive in that dimension to be able to jump?

On another note, when does Nina / Prairie (from the first dimension) become the OA? Has the OA been a dormant spirit within her; has it always been her fate? An entity/self, that she needed to unlock? In that case why has the other Nina not turned into the OA – as in another version of the OA at any point? Is it simply because she didn’t have a near-death experience, that would trigger that in her? Does the OA originate from that particular reality of season one, being exclusive to those specific circumstances, or are there other versions of the “birth” or awakening of the OA?

What would a process of merging consciousness be like? It’s an intricate, unfathomable concept. If you are like me and you’ve ever spent way too much time wondering what it would be like to expand beyond the limits of consciousness and see the world ‘through someone else’s eyes’ (mind), feel it through someone else’s senses, you probably contemplate the mechanism behind this merging and what it would entail, and realise it is problematic.

When the OA travels to the next dimension – if she didn’t succumb to amnesia, would she take Nina’s consciousness with her, since it is implied that by integrating with Nina she becomes, in some way, whole? That would mean that after a few trips into other dimensions, she would contain a collection of different layers of consciousness. Could she live in harmony under those conditions, reconciling the needs, feelings, and wishes of other versions of herself?

Some inspiring, evocative quotes giving a taste of the poetic discourse of the series:

“Captivity is a mentality. It’s a thing you carry with you.”

“Your book showed an openness to liminal thinking. To certain metaphysical secrets that could be glimpsed inside the pain of madness.”

“The process can sometimes help people to heal. Storytelling is cleansing. But I also wanna make sure that you control the narrative. And that you profit from it. The process of telling the story can somehow exorcise it.”

“I can tell you everything that I did wrong. I didn’t eat when I was hungry. Didn’t sleep when I was tired. Didn’t get warm when I was cold. It made me weak. But the biggest mistake I made was thinking that if I cast a beautiful net I’d catch only beautiful things.”

“The first time you fall asleep in prison, you forget. You wake up a free woman. And then you remember that you’re not. You lost your freedom many times before you finally believe it. Night slipped into day. Day into night. We were like the living dead. There’s nothing more isolating than not being able to feel time. To not feel the distance between hours, days.“

“I couldn’t feel pain. I couldn’t sense time. I couldn’t understand where I was. But I could see. The sudden rush of loss made me realise that for the second time in my life…I was dead.“

“You don’t wanna go there until your invisible self is more developed anyway. You know, your longings, the desires you don’t tell anyone about. You spend a lot of time on the visible you. It’s impressive. But she probably thinks the invisible you is missing.”

“I knew from the moment I woke up, that life was no longer the same. Khatun had fed me a mystery. I couldn’t understand it, but I could feel it inside me. A clue, a bomb, a Hail Mary. Oh, we’ve been going about this all wrong. We’ve been trying to get out. We have to try to get in. [into ourselves]”

“I’m telling you, when I swallowed that bird, I felt the whole thing flash through me in an instant. Like, a way to move through the world, through worlds. And if I don’t think about it, I know it. A self, like a…a me in there that doesn’t even belong to me and it wants to come out, it wants me to call it by name. But it’s…I feel like it’s waiting…To hear it in you, too. I don’t know, when I say it out loud, it all falls apart.”

“Are you a feminist?”

“I like symmetry. “

“I thought I was losing my mind.”

“You’re not. You’re just finding new rooms inside it. You’re just having trouble navigating the line between what’s real and what isn’t. Because you empathise so deeply with others. It’s your greatest strength…and your greatest weakness”

“There are all these dimensions, worlds, alternate realities, and they’re all right on top of each other. Every time you make a choice, a decision, it forks off into a new possibility. They’re all right here, but inaccessible. The NDEs were like a way to travel through them, but temporarily. We wanted choices, chances. The movements would allow us to travel to a dimension permanently. A new life…in a new world. To us, that was freedom.”

“What will it look like when we open the tunnel to the other dimensions?”

“All I know is that it would be invisible. The person leaving this dimension would experience a great acceleration of events, but no break in time-space. It’s like jumping into an invisible current that just carries you away to another realm, but we had to have all five movements and we had to do them with perfect feeling.“

“It’s not a game, it’s a puzzle. The designer wants the player to figure it out. It’s not a war…it’s a mystery. Ultimately, a puzzle is a conversation between the player and the maker. The puzzle maker is teaching you a new language. How to escape the limits of your own thinking and see things you didn’t know were there.”

“Cultures that have survived more loss, like harsh weather or earthquakes…they have more totems. Objects carry meaning in difficult times.”

“Well it’s not really a measure of mental health to be well-adjusted in a society that’s very sick. This dimension is crumbling to violence and pettiness and greed, and Steve is sensitive enough to feel it and he’s angry.”